The Royal Botanical Gardens at Kew

As the Royal Botanical Gardens at Kew figure into one of the important scenes in both MURDER AT THE ROYAL BOTANIC GARDENS and MURDER AT KENSINGTON PALACE, I thought it would be fun to take you on a short walk through its early history . . .

The seeds for this spectacular botanical enclave were sowed in the 16th century when Henry VII established a palace and royal hunting grounds on a swatch of land by the River Thames in Richmond. It became a summer retreat for the royals, which in turn drew courtiers to build their own fancy houses in the area.

The area had a setback under Oliver Cromwell, who sold off much of the royal property. However, it was reassembled under William III, and during the 17th century, the first of a succession of eminent English landscape designers began to shape the grounds. William Kent and Charles Bridgeman created the original layout of Kew’s gardens, and later the great Capability Brown added his own signature vision of the ideal Natural World.

By the 18th century, Kew had become the summer residence of the Royal family, who resided in Kew Palace, which had been purchased from a wealthy merchant. Frederick. Prince of Wales, and his wife, Augusta of Saxe-Gotha—parents to the future George III—were not only patrons of the arts but also had an avid interest in gardens. In 1759 they hired William Aiton from Chelsea Physic Garden to create a small “Physick Garden” at Kew, and improvements and experimentation with a variety of plantings made it the leading arbiter of garden design in Britain.

Lord Bute, who had a great interest in landscape design, assisted Frederick and Augusta in envisioning a master plan for Kew. (He also served as a tutor for the young George III.) After George III acceded to the throne, he purchased the Dutch House—a simple brick building now called Kew Palace that still stands on the grounds today—in 1781 to serve as a nursery for his growing brood. His eldest son—“Prinny” for us Regency aficionados—studies botany and drawing there as a child.

But it was the fortuitous friendship that formed between George III and Sir Joseph Banks in the late 1700’s that made the Royal Botanical Gardens such a unique treasure. (I’m a big fan of Banks—I love his curiosity, his sense of adventure, and his sense of fun—excerpts from his diaries of South Seas exploration show a fellow who loved to party with the indigenous people and learn from their local knowledge.) Banks, who went on to be head of the Royal Society, one of Britain’s most august scientific societies, made several expeditions to exotic spots around the globe and brought back many plant specimens.

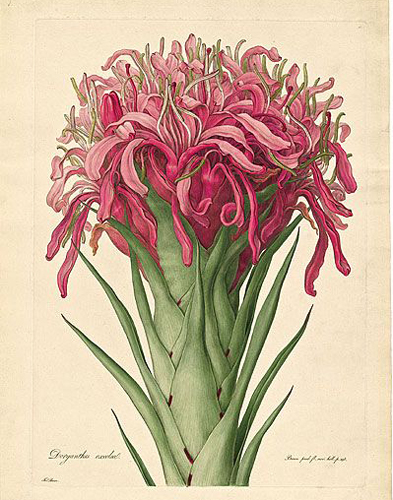

His original collection is the basis of Kew’s amazing variety of plant life. Today, it’s one of the most important botanical research sites in the world. Its seed bank holds over 10% of wild flowering plant species in the world, including nearly every endangered species. The Herbarium houses over 7 million preserved specimens, and its library holds over 175,000 botanical prints and drawings.)