The Portraits of Sir Thomas Lawrence

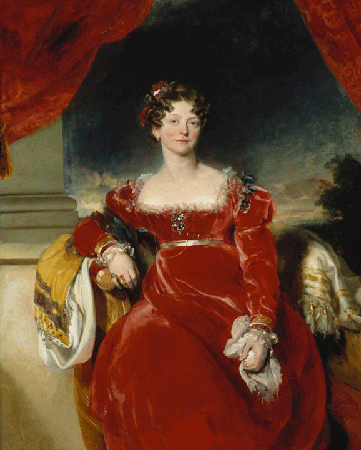

I love the work of Sir Thomas Lawrence, who is considered the premier portrait painter of his time. For me, his brilliance at capturing the nuanced details—the fashions, the ornaments, the styles, the individuality of each person—conjures up the texture, the smell, the feel and the energy of the Regency in all its colorful glory.

Born in 1769, Thomas Lawrence was a child prodigy, a self-taught savant whose formal schooling consisted of two years of attending classes between the ages of six and eight. His father ran an inn in Bristol, but took over the Black Bear Inn in Devizes, a popular stop on the London-to-Bath coaching route, when his own business failed. Travelers would often be asked if they wanted their portraits drawn by the precocious little boy. By age ten, “Tommy” was already being written about in the press.

When his father failed again at business, the family moved to Bath, and from then on, Lawrence supported them with his artistic talents. The charge for a pastel portrait was three guineas, and his sitters included, the Duchess of Devonshire, Sarah Siddons and Sir Elijah Impey. By all accounts, Lawrence was a handsome, charming, modest young man, and popular with his patrons.

In 1787, when he was still seventeen, Lawrence moved to London and set up a studio at 41 Jermyn Street. He had several works in the Royal Academy exhibit of that year, and six the following year, including one oil painting—a medium he quickly mastered. By 1789, his works were garnering favorable acclaim, with one critic calling him “the Sir Joshua of futurity not far off.” (A reference to Sir Joshua Reynolds.) At age twenty he received his first Royal commission, and journeyed to Windsor castle in order to paint the portraits of Queen Charlotte (who did not like the finished work) and Princess Amelia.

On the death of Reynolds in 1792, Lawrence was appointed “painter-in-ordinary to his majesty” by George III, and in 1794, he was made a full member of the Royal Academy For the next 30 years, he would reign as the premier portrait painter of his day, and captured the likenesses of many of the leading luminaries of the Regency.

Through his friend, Lord Charles Stewart, Lawrence became acquainted with the Prince Regent, who became one of his most important patrons. A major commission in 1814 involved doing portraits of some of the top Allied leaders, including Wellington, Von Blucher and Count Platov. Much pleased with the work, Prinny rewarded Lawrence with a knighthood in 1815.

The plan called for him to go abroad and do portraits of some of the leading foreign rulers, but Napoleon’s escape from Elba put that project on hold. However, in 1818, he headed off to Europe where he spent nearly two years traveling and painting the likenesses of such notables as Tsar Alexander, Emperor Francis I of Austria, and the King of Prussia. (These portraits became part of the Waterloo Room at Windsor Castle.)

On his return to London in 1820, he was elected the President of the Royal Academy, a position he held until his death in 1830. His output remained prolific throughout the next decade and his depiction of children during this time is recognized as particularly insightful.

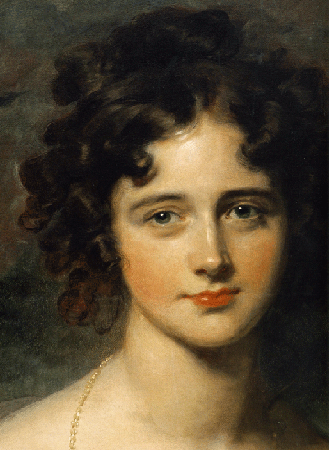

In contrast to the great success of his professional career, Lawrence’s personal life was fraught with disappointment. He was romantically entangled with the two daughters of Sarah Siddons, with his affections shifting from one to the other, and back again. The affairs ended unhappily, and both women died young. Later in his career, Lawrence was linked with Isabella Wolff, whom he had painted in 1803, but he never married.

His finances were also a source of trouble. Though he earned a fortune in commissions, he was constantly in debt—though his biographers are puzzled as to where all his money went. Lawrence himself claimed, “I have never been extravagant nor profligate in the use of money. Neither gaming, horses, curricles, expensive entertainments, nor secret sources of ruin from vulgar licentiousness have swept it from me.” And most people agree. It’s thought that his great generosity to his family, and his magnificent—but expensive—collection of Old Master drawings ate up most of his earnings.