The History of Chocolate

Chocolate. The word sends sweet shivers of craving through most of us. Whether it’s consumed as a sweet or a savory, as a solid, a beverage, an ingredient in baked goods or sauces, few foods are as beloved. (And BTW, there is a medical reason for such euphoria—chocolate contains chemical compounds that stimulates the brain to release endorphins, which stimulate a sense of well-being in us. But more on its medicinal properties later!) So it’s no mystery that its history is as rich and delicious as its taste. Chocolate figures prominently in my Lady Arianna series—both she and Lord Saybrook are connoisseurs. Now, many people think that edible chocolate did not exist in the Regency. But history shows that it did! Just read on . . .

First of all, a few basic facts about Theobroma cacao (the scientific name for the plant that produces the beans.) There are three distinct types of cacao trees. Criollas are considered the ‘prince of cacao.’ They are very delicate and prone to disease, but produce the highest quality beans. Forasteros are the most common variety and although they are very hardy, they are the least flavorful. Trinitarios, named for the island of Trinidad, are a hybrid, and offer an excellent balance of taste and ease of cultivation. It is a tropical plant that grows roughly within a band 20 degrees north and south of the Equator, and originated in the New World, where the first archeological evidence shows it was used by the Olmec culture, which flourished in present-day Mexico from c. 1200-300 BC.

Chocolate came to be revered in Mesoamerican culture. According to ancient Aztec legend, the cacao tree was brought to Earth by the god Quetzalcoatl, who descended from heaven on the beam of a morning star after stealing the precious plant from paradise. It’s no wonder that the spicy beverage made from its beans was called the ‘Drink of the Emperor.’ It is said that this xocoatl or chocolatl was so revered that it was served in golden goblets that were thrown away after one use.

Chocolate was served during religious rites and celebrations. It was often mixed with flavorings such as vanilla, cinnamon, allspice, chilis, hueinacaztli—a spicy flower from the custard apple tree—and anchiote, which turns the mouth bright red. The Aztec also believed that cacao possessed strong medicinal properties—indeed, warriors were issued solid cacao wafers to fortify their strength and endurance for long marches and the rigors of battle.

The legend of Quetzalcoatl also held that the he was banished from Earth for bringing the gift of chocolate to mankind, and that one day, he would return in glory. So when the Spanish conquistador Hernan Cortez and his fleet sailed over the horizon in 1519, the Aztecs thought he was the ancient god. Alas, poor Montezuma! Though it is recorded that he drank 50 cups of chocolate a day, his magical military elixir proved no match for guns and horses.

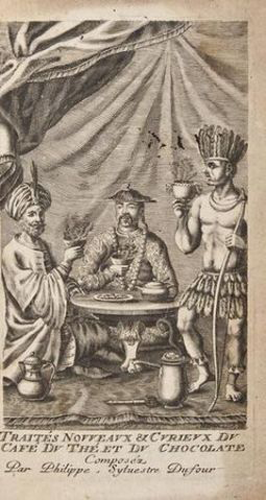

The earliest mention of chocolate in Europe occurred in 1544, when a delegation of Dominican friars returned from Guatemala and presented Philip II with a pot of hot, frothed chocolate. His reaction is not recorded, but I have learned that the Spanish found the Aztec preparation too bitter and spicy for their taste, and so began adding sugar from the cane plantations in the Caribbean islands. They also began to use a molinillo, or whisk, to froth the drink, instead of pouring it back and forth between two cups, as was the Aztec method. (The traditional chocolate pot, invented in the 1600s, has a hole in it lid to allow a molinillo.)

The Spanish kept chocolate their own private secret for many years. (English pirates who preyed on the Spanish treasure fleets sailing from the New World once burned an entire cargo of cacao beans, thinking they were sheep turds!) But by the late 1500s, chocolate had spread to Austria and France. Although there is some debate about how chocolate was introduced into France, the credit most likely belongs to Anne of Austria, daughter of King Philip III of Spain. It is said that that she gave her husband an engagement present of chocolate, packaged inside an ornately decorated wooden chest. (A sweet story, even if it isn’t true.)

Chocolate soon became very popular in Catholic countries because Pope Pius V ruled that drinking the beverage did not break the fast, and so it could be taken as nourishment on Holy Days. (Theobroma cacao played a more sinister role in Church history in 1774 when Pope Clement XIV was murdered by the Jesuits, who poisoned his cup of chocolate.)

The first record of chocolate being used as a medicine came in 1570. Francisco Hernandez, the royal physician to King Philip II, believed that it was beneficial, and prescribed it to reduce fevers and relieve discomfort in hot weather. During the 1600s, Francesco Redi, personal physician to Cosimo III of Florence and one of the leading scientists of his day, spent time experimenting with the creation of decadent recipes for chocolate. Some of his concoctions included drinks perfumed with ambergris, musk and jasmine.

Chocolate finally arrived in England by the mid 17th century. It’s interesting that coffee from the Middle East and tea from the Orient arrived around the same time, and chocolate was the most expensive of the three. Still, it became popular, especially among the elite of London, despite the cost. Samuel Pepys, the great chronicler of his time, made regular mention in his famous diaries of drinking chocolate. By 1700, there were over 2,000 chocolate houses open in London. In fact, White’s, the legendary gentlemen’s club, was originally established by an Italian immigrant, Francesco Bianco—Francis White—who opened White’s Chocolate House in 1693. In 1728, the Dutch developed a special grinding machine designed to create smoother, finer chocolate. (Clever people, those Dutch!)

Now, recently I have seen a tempest in a chocolate pot swirl on some of the Regency loops regarding edible chocolate. Some people have scolded writers who include such treats in Regency stories, saying it is historically inaccurate. Well, I beg to disagree. My research has shown that chocolate was definitely being consumed in solid form by the late 1700s. In fact, several years ago I interviewed the U. S. head of the French gourmet chocolate company Debauve & Gallet who provided these tantalizing tidbits of chocolate history.

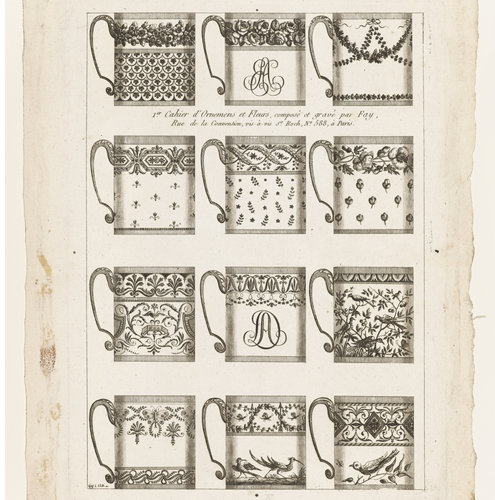

Sulpice Debauve, was a chemist who served a pharmacist to King Louis XVI. On one of his visits to the royal family, Marie Antoinette complained about the unpleasant taste of her medicines. Debauve came up with the idea mixing it into a solid form of chocolate—a pistole or wafer-like disc that the Queen is said to have adored. (The company still offers Pistoles De Marie Antoinette . . . a 1.7 lb box costs the princely sum of $200.)

The pistole was first made of cocoa, cane sugar, and medicine mixed together. However, as the queen became enamored with her new sweets, she asked for more variety in tastes. So Debauve became, in essence the first “chocolatier” as he created bonbons with such flavorings as orange blossom, almond milk, Orgeat cream, coffee and vanilla. It’s believed that the queen’s favorite was almond milk.

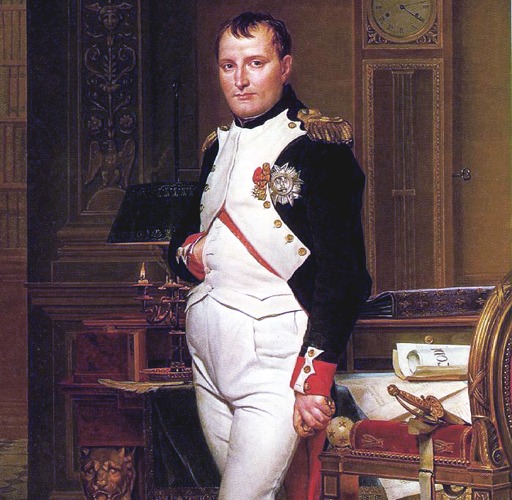

Unlike his royal patrons, Debauve survived the revolution and in 1800 he opened his first chocolate shop on the left bank of Paris. By 1804, he had more than 60 shops throughout France. The company claims that legendary chef Antoine Carême and Debauve occasionally worked together, and that the idea for croquamandes—caramelised almonds coated with dark chocolate—resulted from a discussion between the Napoleon and Carême about creating a special treat to celebrate the Battle of Friedland victory in June of 1807. Debauve supposedly went back to his kitchen and voila—a few days later delivered the first croquamandes to the Emperor, who became yet another of history’s chocoholics.