Regency Aviators

In doing research for my third Lady Arianna mystery, A Recipe for Treason, I came across a wonderful book entitled The Age of Wonder—How the Romantic Generation Discovered the Beauty and Terror of Science. The author, Richard Holmes, creates a vivid picture of a wondrous time—he paints captivating portraits of pioneer scientists and through fascinating—and often amusing—vignettes explains how their discoveries profoundly affected the world around them, influencing art, literature, music, politics, and religion. In other words he made science really come alive!

By fortuitous coincidence, I saw that Holmes was giving a lecture near my home, so off I went to hear him. I’m delighted to report he spoke with the same passion and humor with which he writes. He ended his talk by saying his mission is to make people realize that science isn’t a dull, dry compilation of arcane formulas and boring tables. Like the arts, it’s about curiosity and creative genius, imagination and courage, faith and, yes, humor.

A section of the book is devoted to early flight—hot air and hydrogen balloons, and the daring aeronauts who ventured into the skies. And it was so interesting that I was inspired to include aeronautics as part of the plot of my mystery! So for a little background on the subject, let’s take a quick flight through early aviation history.

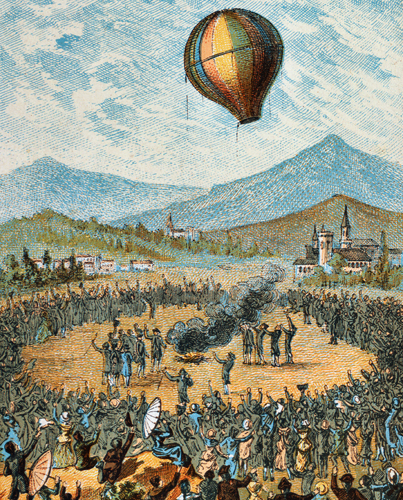

The Montgolfier brothers, Joseph and Etienne, were French paper manufacturers with an interest in chemistry. Inspired by watching his wife’s chemise inflate while drying by the hearth, Joseph conceive that his company could make flying machine out of very large paper bags filled them with hot air—or the new “inflammable air” (hydrogen.) He and his brother tested the idea by sending up a sheep, duck and a cockerel in a wicker basket attached to a beautifully decorated balloon. (They referred to it as “putting a cloud in a paper bag.”) When the animals came back down to earth unharmed, the space race was on!

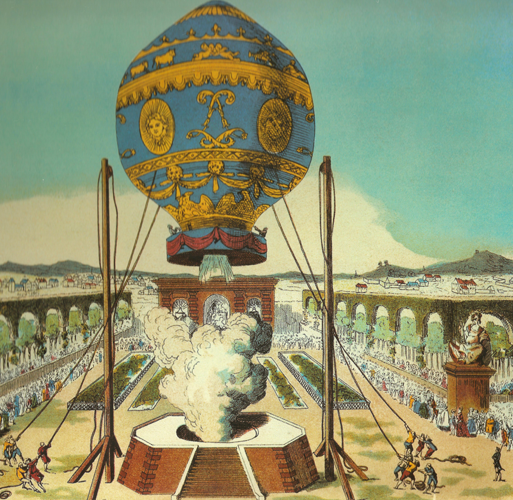

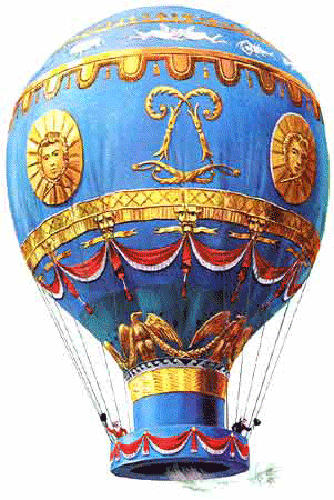

Their first manned flight—piloted the swaggering, skirt-chasing Jean-Francoise Pilatre de Rozier—was launched on November 21, 1783. It was colored a glorious sky blue and stood over 70 ft high. An open brazier burning straw provided the lift-off. He was joined by the Marquis d’Arlandes who provided a counterweight as well as muscle to stoke the fire. The 27-minute flight was apparently a comic ballet as the balloon floated over the rooftop of Paris, narrowly missing the church steeples and windmills as Pilatre kept warning the marquise to stop admiring the view and keep shoveling!

Across the Channel in England, the Royal Society was not happy that their Gallic confreres were stealing the show. (Partly because even back then, people were quick to realize the military implication of flight. Benjamin Franklin calculated that 5,000 balloons carrying two men “ . . . might in many places do an infinite deal of mischief before a regular force could be brought together to repel them.”) It was, however, an Italian who pioneered English ballooning. On September 15, 1784, Vincent Lunardi took off from London on the first manned ascent from British soil, observed by a cheering crowd that included the Prince of Wales. Drifting over the countryside, he enjoyed a meal of cold chicken and champagne while once in a while attempting to “row” his contraption with a pair of oars. A marketing genius, Lunardi had raised money for his exploits by exhibiting his red-and-white striped balloon at the Lyceum Theater before the launch, charging 2 shilling, sixpence for a visit.

He became an instant celebrity after the flight, selling his story to the Morning Post, and spawning a host of trinkets with his likeness—cups, snuffboxes and ladies’ garters were great favorites. Ever the showman, Lunardi then went on to invite the first female “aeronaut” to join him on a flight.

The actress Mrs. Sage played the starring role, along with a dashing Old Etonian named George Biggin. The gondola, a lavish affair draped in heavy silk, had some trouble getting airborne (Mrs. Sage later said she had lied about her weight and Lunardi was too much of a gentleman to press her.) In any case, there was much scrabbling about in the cockpit, leading to speculation on the ground of whether the Mile High Club was conceived on that first co-ed flight. After floating above the Thames for a while, the balloon fell to earth and was dragged through a field and into a hedge by the wind. Students from Harrow, which was close by, rushed out to rescue Mrs. Sage, who had injured her foot, and carried her off to a nearby tavern where “everyone evidently got gloriously drunk.”) The event inspired the members of Brooks to start placing bets on who would be the first to have “an amorous encounter” in a balloon.

The stories get even better as the race to be the first to cross the English Channel heated up. Both countries were rushing madly to prepare for a try, but the British balloon launched first. It was manned by an American, John Jeffries, and a Frenchman, Jean-Pierre Blanchard (an inventor in his own right who had experimented with different ways to steer flight, including oars, flapping wings and a primitive propeller.) The flight itself was a wild ride, and as the balloon began losing altitude, the two men stared throwing things overboard. Out went the brandy bottles—after they had drunk the brandy. Next went their clothes (Jeffries has started out wearing a very natty beaver flying hat and chamois gloves, an early exponent of ‘aviator cool.”) Once they had stripped down to their only their drawers, the balloon began to stabilize. Finally, after furiously emptying their bladders, they made it to a dry landing in France—a triumph of the human ingenuity and pluck!

I hope you’ve enjoyed this tiny glimpse into heady first days of “modern science!” As you can see, there was nothing stuffy about these experiments!