David Hosack and Botanical Gardens

I first met David Hosack in American Eden—David Hosack, Botany, and Medicine in the Garden of the Early Republic, Victoria Johnson’s marvelous book on America’s first botanic garden.

Born in New York City1769, David Hosack was the son of a well-to-do merchant from Elgin, Scotland and his wife. He was educated at Columbia College, where he became fascinated with the study of medicine. He finished his studies at the College of New Jersey (now known as Princeton) and then went on to study medicine in Philadelphia, where he wrote his doctoral thesis on cholera. In 1791, he married and started a private practice in Virginia, but then returned to New York City a year later.

Convinced that the best physicians had all studied in Europe, he cajoled his father into paying for further medical studies in Britain. It’s there that Hosack discovered his lifelong passion for medical botany and its ability to cure many of the ills that plagued the world. His studies at the University of Edinburgh introduced him to the well-known botanic garden in the city. But it was when he moved on to London and engaged to study with William Curtis, who ran the Brompton Botanic Garden, that he was inspired to dream of bringing medical botany to America.

Curtis was the perfect teacher for Hosack. While many continental botanists were loath to embrace the new plant classification system designed by Carl Linnaeus as part of his Systema Naturae, Curtis quickly adopted it and made it popular in Britain. He recognized that it revolutionized the field of medical botany in two basic ways. Traditionally, plants all had local names, so when botanists from different regions or countries tried to share their knowledge about the healing properties of plants, it was impossible to communicate!

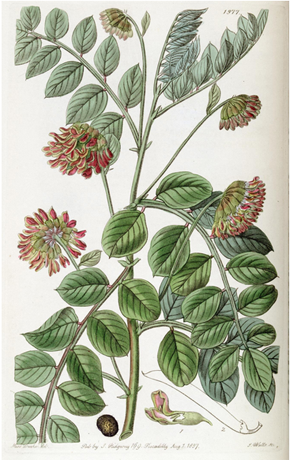

Secondly, the idea of classifications like ‘species’ and ‘genus’ allowed botanists to recognize plants with similar characteristics and explore their medicinal possibilities in an orderly, scientific way.

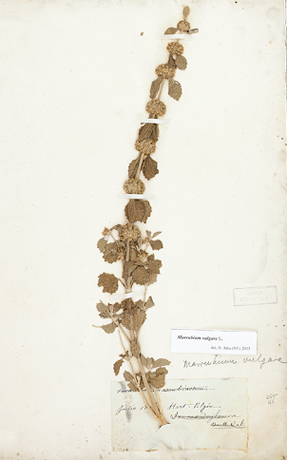

Curtis also collected field specimens and made up individual cards with an example of a dried plant and its medicinal characteristics. This he used as teaching aids to educate students, who then could go home and use that knowledge for healing. He also propagated specimen medicinal plantings at his Brompton Garden and sent them around the world to other botanical gardens. The Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew were also a leader in disseminating this type of knowledge on an even greater scale. Merchant ships arriving in London from exotic ports of call would often bring specimens for the Royal Collections, which in turn would share them with other scientific establishments.

Flush with excitement over all he had learned in Britain, Hosack returned home to New York City determined to establish the first botanic garden—the medical botany—in America. It was, to say the least, a labor of love. He spent a fortune of his own funds in hiring young men to help him scour the countryside around the city, collecting both plants he recognized from Britain and new American species. (Some of his original collection cards are at the New York Botanical Society.)

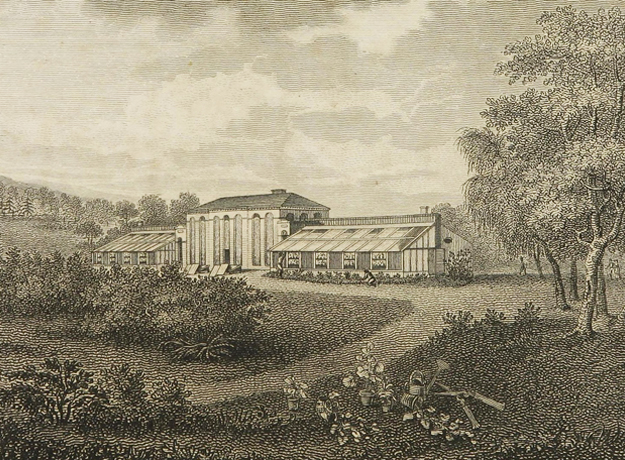

He was well-connected in New York society, and worked to get the state government to help fund the project. While he did eventually get some monetary help, he shouldered most of the cost for buying a tract of wild land several miles outside the city, and worked alongside hired hands in doing the manual labor to bring his dream to fruition.

The Elgin Botanic Garden—named for his father’s hometown in Scotland, was a milestone in American medical history, and inspired a new generation of physicians to explore the country’s treasure trove of plants for healing medicines. Much knowledge was gained from Native Americans and incorporated into what the men like Hosack were discovering on their own. Plant field guides proliferated, and new medicines were discovered through scientific study.

By 1810, Hosack was busy with his private practice, many philanthropical projects and scientific societies, and so decided he couldn’t continue to keep the garden going on his own. He negotiated its sale to the state of New York—at a great financial loss— and the state passed it on to Columbia College in 1814. Alas, the college let it go to seed, and the magnificent garden eventually disappeared. The land itself was ended up being leased to John D. Rockefeller, who in the 1920s built Rockefeller Center on Hosack’s original garden. (Today there is a small plaque on one of the benches acknowledging its place in history.)

I found Hosack and his passion to create a botanic garden to heal people be a real feel-good story, and had such fun working him in as a character in MURDER AT THE ROYAL BOTANIC GARDENS, the fifth book in my Wrexford & Sloane historical mystery series.