Regency Satirical Prints

These days, it’s hard to read a publication or watch television without getting bombarded with stories about a movie star’s misbehavior or a politician’s sexual shenanigans. But our current fascination with gossip and scandal is nothing new.

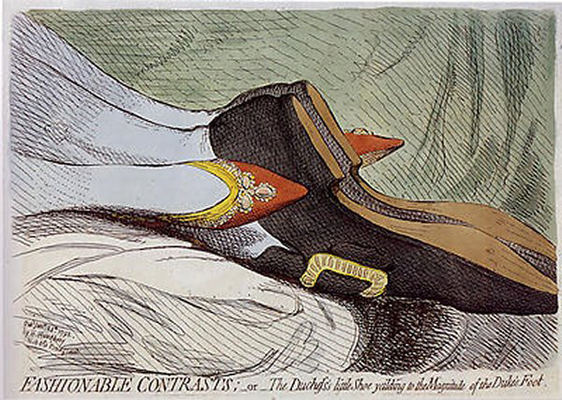

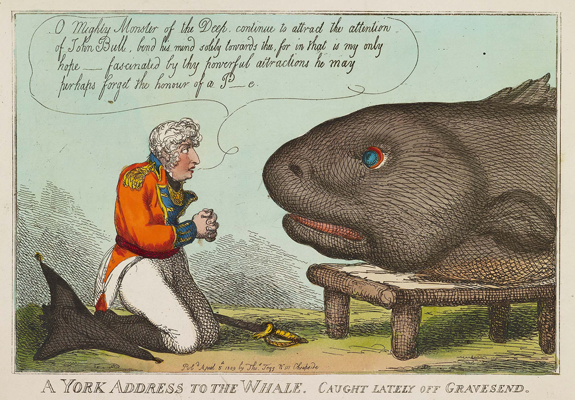

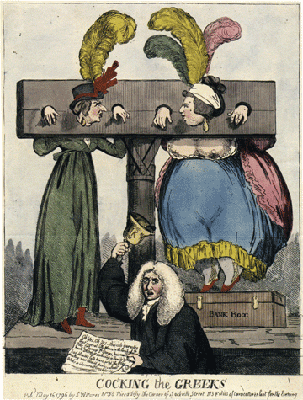

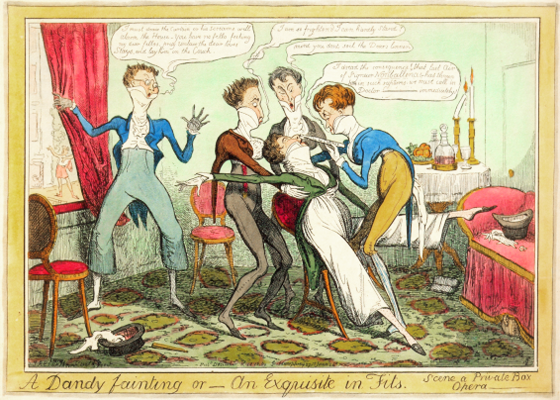

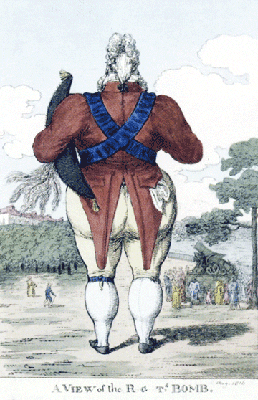

Regency England reveled in ‘tittletattle,’ and had its own colorful scandalsheets and “paparazzi.” Newspapers and pamphlets reported in lurid detail on the celebrity bad boys—and bad girls—of high society. Like today, sex, money and politics were hot topics. As for pictures, there were, of course, no cameras to capture candid snapshots and personal transgressions. But the artists of the Regency could be even more cutting than modern-day photographers, and their sharp wit make them famous in their own right. (Here are just a few examples:)

In Murder on Black Swan Lane, the first book in my Regency-set “Wrexford & Sloane” mystery series , the heroine is London’s most popular—and scathing—satirical artist. So naturally, I decided to do a little research into the subject. I’m lucky enough to live close to the British Art Center at Yale, which has an amazing collection of vintage Regency prints in its study room.

You can make an appointment, sort through the card catalogues to decided what you want to see—and voila! The boxes are brought to your work table. The chance to study originals was a wonderful experience. (Not to speak of getting to sort through a whole box of J. M. W. Turner’s watercolor sketches of his trip through the Alps with my hot little hands—well-washed of course. They make you scrub!) To see the actual colors and richness of detail is, well, eye-opening.

The art of satire was honed to a fine edge by London’s top printmakers, who were masters at creating caricatures of famous figures of the day—anyone from leading politicians to notorious courtesans—as well as crafting commentaries on current events. The prints were widely available at printshops all over Town, and were wildly popular with the public, who ate them up, gleeful at seeing their betters—or their peers— exposed to ridicule.

As for politics, the printmakers captured public sentiment on war, taxes, and other controversies. Often irreverent, sardonic and scathingly funny, their work provides a wonderful mirror of the social and cultural temper of the times.

According to Vic Gatrell in his book City of Laughter, 20,000 satirical prints were published in London between 1770-1830. He calls those years the Golden Age of Graphic Satire, for after 1830, new printing technologies made hand-colored engravings obsolete as a means of social commentary. Three of the most famous print artists from the Regency were James Gillray, Thomas Rowlandson and George Cruikshank, who all followed in the tradition of William Hogarth, one of the great English satirists of the 18th century.

James Gillray was born in Chelsea and trained as an engraver of letters. He grew bored and left to spend several years with a troop of strolling players (which may be where he developed his humor.) Returning to art, he was admitted as a student to the Royal Academy, and began supporting himself by creating caricatures. His publisher and printseller was Miss Hannah Humphrey—and she was also his mistress. Gillray lived with her throughout his career.

Some of his most scathing satire was directed at King George III, who once said, “I don’t understand these caricatures.” Like the king, Gillray descended into madness and died in 1815.

A good friend of Gillray, Thomas Rowlandson was from a well-to-do family and attended Eton. From there, he became a student at the Royal Academy and spent two years in Paris honing his drawing skills. In 1777, he set up his own studio in Wardour Street, where he worked as a portrait artist, as well as a chronicler of daily life. A keen traveler, he also recorded his impression of his trips to the Continent.

Rowlandson didn’t prosper as a painter and so sought employment as an engraver at Ackermann’s print shop. In 1808, he collaborated with Randolph Ackermann on a series of books on London life. He was a heavy gambler, and in his later life, he often paid his debts with drawings.

George Cruikshank had art in his blood—his father was the well-known Scottish painter and caricaturist, Isaac Cruikshank. He earned fame for his comic illustrations for “Life in London,” a landmark Regency satirical book that followed three young men through the the city, where they experience the highs and lows of its pleasures.

The Regency artists were all greatly influenced by William Hogarth, who was one of the most important print artists of the 18th century. His observations of the world around him were gritty and unflinching, and by portraying reality, warts and all, he inspired the new generation of artists to add even more color to their era.