The Art of British Watercolors

My background is in art, and having dabbled in watercolor color painting, I was especially excited about exploring its history during the Regency era. So twirl your sable brushes to fine point, add a wash of pigment to your cold pressed paper and let’s sketch in a quick outline of the early nineteenth century art scene in Great Britain. (Scroll your cursor over the bottom of each picture in the slideshow to see the name of the artist.)

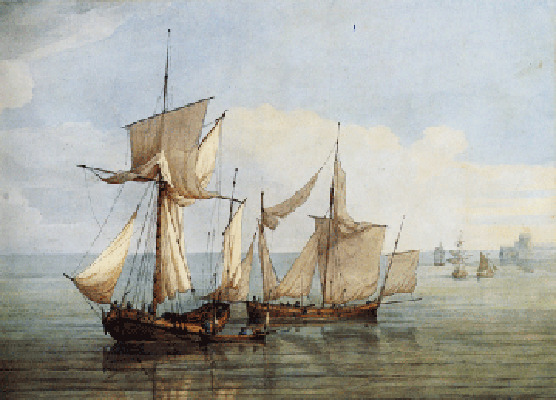

The country has an incredibly rich heritage in watercolor painting, and, as is true in so many other fields, the Regency was a time of great energy and evolution as artists began to look at their world in a whole new way. In previous centuries, watercolorists were considered more as draftsmen than true artists, and often worked with surveyors and mapmakers. Their work was considered utilitarian, more a record of topographical information—how a town or a countryside or cathedral looked—than a creative work.

That began to change as techniques loosened and became more expressive. The traditional style was known as the “stained glass” method, in which ink outlines were carefully colored in with washes of pigment. But watercolors, as opposed to oil paints, are by their very nature spontaneous. They dry very quickly, so an artist must work fast. yet, they are also transparent, so one can build color, change tones, add details, slowly building an organic image of luminous beauty.

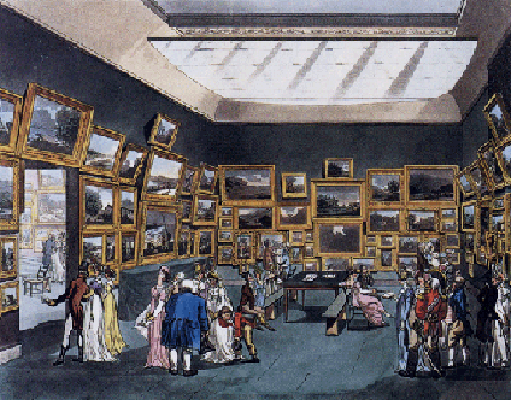

The change in attitude actually began in 1760 when watercolor artists were first allowed to exhibit their painting in the annual public art exhibitions. The Royal Academy, which was founded in 1768, also recognized the medium, but for the most part, its practitioners were treated like second class citizens. So in 1804, a group of artists banded together and made a bold move, establishing the Society for Painters in Water-Colours. By proclaiming their own special status and organizing their own exhibitions, they in effect through down a gauntlet to the rest of the art world—and won recognition with both their peers and the paying public.

The shows were, in the words of Great British Watercolors, by Matthew Hargraves, “critical, popular and financial successes.” Indeed, William Marshall Craig gave a series of lectures at the Royal Institution in London in which he categorically claimed that watercolors were far superior to oil painting. The debate was a heated one throughout the first few decades, with noted periodicals such as Rudolph Ackermann’s monthly Repository of Arts featuring a series of essays on the subject in 1812. Of course no consensus was reached—the important point was that watercolorists had succeeded in establishing themselves as a serious players in the art world.

You may all recognize the name of J.M.W. Turner, who is perhaps the most famous watercolorist of his era. His innovative, impressionist style—which still appears incredible modern—helped revolutionize painting as a whole, but there were also equally talented artists who are less well-known, especially to an American audience. Here are just a few of the notable names:

Alexander Cozens (who was really a Georgian, but I’m taking artistic license) taught for years at Eton. In addition to producing hauntingly beautiful works of his own, rendered in an austere, monochromatic palette, he shaped the artistic tastes a whole generation of English aristocrats . Two of his pupils, Sir George Beaumont and William Beckford, are recognized as two of the greatest collectors and connoisseurs of their age.

Thomas Girtin trained with Turner at Munro’s Academy and while his work appears more traditional than that of Turner, his exploration of texture, shadow and color established him as a leading practitioner of the medium. Unfortunately an early death, at age 27, cut short a brilliant career.

Richard Parks Bonington was another brilliant artist who died of consumption at an early age. His fluid style and observant eye make his paintings a wonderful source for the little details of everyday life.

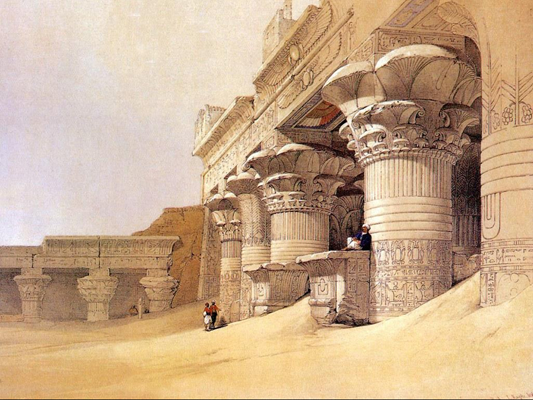

David Roberts became one of the leading “travel” artists, a genre which appealed greatly to a Regency audience who were in love with exotic places. His works were most of the East, which seemed to have a special allure to his viewers.

While the majority of watercolorists were landscape artists, Thomas Rowlandson was a luminary of the figurative art. A famous satirical printmaker as well as a painter, Rowlandson captured scenes of daily life with a eye for every boisterous, bawdy detail.

I hope you have enjoyed this oh-so brief peek at the fabulously rich and diverse world of British watercolors.

Now, many of you have probably dabbled in “watercolors.” But the stuff of grade school art class is a far cry from the “real” thing. So here is a quick primer on the materials and techniques that Regency artists used to create their richly nuanced paintings.

As opposed to oil paints, watercolors are transparent, and an artist builds color, texture, depth and shadow by layering washes of pigment. (There are opaque watercolors, which are made of pigments mixed with white zinc oxide—these are called “bodycolor” by the English, but are more commonly known by the French name of “gouache.” However, that’s another subject!) Transparent watercolor “paint” is made up of finely ground mineral or organic particles, bound together with two main additives: gum arabic, which helps adhere the pigment to the paper, and oxgall, a wetting agent which helps disperse the pigment in an even wash. In Regency times, the pigments were formed into solid square, or cakes, which would be carried in a wooden paint case (Tubes of viscous paints were invented by Windsor and Newton in 1846.)

An artist would dip his brush in water, then dab it over the block of pigment to dissolve the pigment. The amount of water used determines the intensity of the color. Most artists start with very light washes to lay in the basic elements of their composition, then build depth and details. There are a vast array of pigments, and their names are wonderfully evocative on their own—alizarin crimson, yellow ochre, Vandyke brown, cerulean blue, to name but a few.

If you look closely at a watercolor painting, you may see a faint tracing of lines beneath the color. Many artists used graphite pencils to make a preliminary sketch of their subject. Charcoal (the solid carbon residue from charred twigs heated in an airtight chamber) or black chalk (carbon mixed with clay and gum binders) were also used. They produced a softer, but usually darker line. For some artists, these line sketches were deliberately strong and were used as an integral part of the finished painting.

Paper is an important component of a watercolor painting because its texture affects the look of the washes. James Whatman created “wove” paper in the 1750s, which quickly became popular with artists. Wove paper uses a fine wire mesh screen as a mold, making a finer surface than the earlier “laid” papers. This allowed a more uniform wash. (Whatman is still a very highly regarded brand today.) The paper made by Thomas Creswick, which offered a rich assortment of textures, was also popular. Another favorite was “scotch” paper, made from bleached linen sailcloth. It had a more rustic feel, and featured imperfections such specks of organic matter that some artists felt added interest to their paintings.

Brushes are made from a variety of furs. During the Regency, squirrel was favored for soft, wide brushes designed to lay in broad washes. But the very best ones were made of asiatic marten—or Russian sable—as they held their shape very well and could be twirled to a very fine point in order to paint in detail.

I hope this quick sketch adds to your enjoyment next time you are viewing a watercolor in a museum or gallery.